The First World War was a global conflict fought from 1914 to 1918. It was one of the bloodiest wars in history with around 16 million people killed and many more wounded.

In the late 19th century, rivalries developed in Europe over establishing colonies in Africa. European powers believed there was national prestige, as well as wealth, in having an empire. Tensions grew as they built up their militaries and made alliances to defend them. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy formed the Triple Alliance. To counter it, Russia, France, and Britain signed the Triple Entente.

In preparation for war, nations carried out military exercises with their armies. The last peacetime drills in Britain took place in Northamptonshire in September 1913. The troops stayed in camps set up around the county and even King George V came to watch. Using a scenario between fictional countries (based on the situation in Europe), the exercises tested and improved the army.

The outbreak of war

On 28th June 1914, a Bosnian Serb assassin shot the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The Austrians presumed it was part of a larger plot and invaded Serbia. Due to the web of alliances, most of Europe was at war within a week. Other nations joined later, including Britain’s colonies. Almost a third of the troops fighting for Britain came from the empire.

In Britain, people believed that victory would be swift and the war would be over by Christmas. Fired by patriotism, young men volunteered en masse. There was also a lot of pressure to join and those who didn’t were treated as cowards. Edgar Jarvis from Stanwick joined the Northamptonshire Regiment in 1915. He wrote to his sister: "I thought I would go and show willing rather than stop at home and be called a coward." Like hundreds of thousands of others, Edgar was killed during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

In Britain, people believed that victory would be swift and the war would be over by Christmas. Fired by patriotism, young men volunteered en masse. There was also a lot of pressure to join and those who didn’t were treated as cowards. Edgar Jarvis from Stanwick joined the Northamptonshire Regiment in 1915. He wrote to his sister: "I thought I would go and show willing rather than stop at home and be called a coward." Like hundreds of thousands of others, Edgar was killed during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Victory was not swift, and by Christmas, men were digging themselves into trenches for the long haul. As more and more men were killed, fewer volunteered, and in January 1916, the government introduced conscription.

Military exemptions

At first, only single and widowed men aged 18 to 41 were conscripted. Later, this was extended to all men aged 18 to 51. However, men could apply for an exemption. Tribunals assessed cases and could give a full, temporary, or conditional exemption for a variety of reasons.

Less than 10% of the 250,000 applications nationwide came from conscientious objectors. Most were required to take on non-fighting duties in the military. Others, like Fred Paling, a junior railway porter from Kettering, received a full release. On his appeal, he wrote: "I feel that non-combatant service is still an essential part of the military machine."

Almost half of all exemptions were given to alleviate hardship. Many others were granted to men with important jobs to try to balance the needs of local economies with the war effort. In Northamptonshire, agricultural and shoemaking workers were most likely to receive exemptions. For example, Thomas Spendlove of Gretton won a temporary exemption for his third son, Frederick, on the grounds that he was needed as a boot maker.

Sometimes people disagreed with an exemption. George Farey asked for an exemption as the only remaining son of his widowed and disabled mother. However, a soldier’s wife wrote to the Northamptonshire appeals tribunal saying: "He is trying to hide behind his mother to save his own skin and enjoy the liberty that men with big families are laying down their lives for."

Combat

Over 800,000 British soldiers, 5,620 of whom were from the Northamptonshire Regiment, laid down their lives in the course of the war. The deadlock on the Western Front led to huge numbers of casualties to gain only a few hundred yards of ground. Alexander Morley from Great Brington, a private in the Northamptonshire Regiment, recorded the violence in his diary. On 27th June 1916, he wrote:

And the Germans cast their flare lights at us from their trenches and in the midst of the banging and uproar and the shells lighting everywhere and flying everywhere, we could see the great fountains of smoke cast by the latter where they landed. […] And while we were there, down the little knots of fearful men came the order by mouth for stretcher bearers, and the knowledge of casualty added the terror of death to the horror of bombardment.

Furthermore, trench warfare meant that soldiers lived for periods in cold, muddy ditches. Lice and disease spread easily. Alexander described how they lodged in dugouts "where everything we touched was muddied and where everything was mud, wet slimy mud, and where the ooze dripped through on us and where to be down was to lie soaking in mud."

Civilians did not escape bloodshed either. German airships raided Northamptonshire 29 times, dropping 66 bombs. In October 1917, the Zeppelin L45 airship dropped a bomb on Northampton, killing Eliza Gammons and her 13-year-old twin daughters.

Civilians did not escape bloodshed either. German airships raided Northamptonshire 29 times, dropping 66 bombs. In October 1917, the Zeppelin L45 airship dropped a bomb on Northampton, killing Eliza Gammons and her 13-year-old twin daughters.

The wounded come home

Thousands of wounded soldiers were cared for in Northamptonshire. The authorities received daily telegrams from Dover advising how many casualties to expect. Patients would arrive by ambulance train to

Castle Station, in Northampton. The authorities then decided to which hospital patients would be sent.

Northampton General Hospital had erected wooden pavilions in the grounds. They had 120 beds and treated 3,094 patients over the course of the war.

Other buildings were also taken over to cope with the volume of wounded servicemen. Barry Road School became a hospital with 260 beds and treated 4,370 wounded. Similarly, Abington Avenue School had 64 beds and cared for 1,560 patients.

The largest hospital in town, Berrywood Asylum (later known as St Crispin’s Hospital), became Duston War Hospital during the war. The inmates of Berrywood were transferred to other asylums and the hospital cared for 25,000 wounded soldiers instead.

Hundreds of local residents supported the authorities with lodging, voluntary nursing, and outings for the wounded.

The wider war effort

Civilians also worked for the war effort and factories across the county made uniforms, guns, and ammunition. The National Filling Factory Number 9 in Warkworth, built in 1916, was one of the earliest purpose-built munitions factories. It employed around 2000 people, most of whom were women workers known as ‘munichionettes’.

With so many men serving in the armed forces, women were needed to replace them in factories, on farms, and elsewhere. Around two million women took jobs that had previously been reserved for men, including non-fighting roles in the armed forces.

With so many men serving in the armed forces, women were needed to replace them in factories, on farms, and elsewhere. Around two million women took jobs that had previously been reserved for men, including non-fighting roles in the armed forces.

Women also organised welfare groups. At the beginning of the war, thousands of Belgian refugees arrived in Britain and committees were set up to help them. For example, the Stanwick committee raised funds and the Kettering committee organised treats, trips, and work for refugees. Another group raised money and sent parcels of food, clothing, and tobacco to local men held in German Prisoner of War (POW) camps.

Northamptonshire itself was home to dozens of British POW camps. These housed German and Austrian civilians living in Britain, as well as captured enemy soldiers. Eastcote Camp (later renamed Pattishall Camp) was set up for German merchant seamen who worked on British ships. Later, it held 4000 military POWs. One inspection noted that there was little reason for escape because the conditions were comfortable. However, over the course of the war, eighteen POWs tried to escape. The first, Alfred Stockhurst, only made it to Foster’s Booth - less than one mile away. Alphonse Griem made a better attempt to escape from Pen Green Camp near Corby. He made it all the way to Dieppe in France before being recaptured. The POWs returned home at the end of the war.

The end of the war

The war ended at 11am on 11th November 1918. Cyril Day, a Sergeant in the Northamptonshire Yeomanry, described the truce in his diary:

Just before reaching the river, the Italians told us to stop on account of an armistice being signed with Austria… Whole divisions of the Austrians were laying down their arms just over the river. It was one of the strangest things I ever knew, no one knew what to say. The news that the fighting was over, coming so suddenly and unexpectedly, seemed too good to be true. I could only kneel down in front of my horse and thank God.

The war ended with victory for Britain and its allies, but had caused global devastation. Around 16 million people had been killed and many others returned home disabled. East Carlton and Woodend are known as ‘thankful villages’ because they were the only places in Northamptonshire that did not lose any military personnel in the war. Over 500 memorials were built across Northamptonshire to help families and communities grieve.

Acknowledgements:

The Battle of Passchendaele, 1917 ©

IWM (Q 2978), licenced under the

IWM Non Commercial Licence

Edgar Mobbs ©

The Northampton Saints

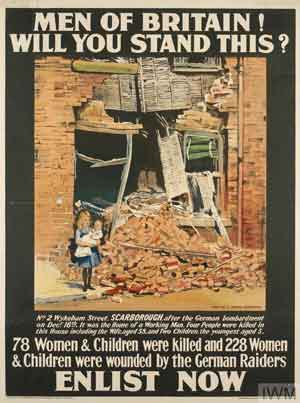

Men of Britain! Will you Stand This? Recruitment poster, 1915 ©

IWM (Art.IWM PST 5119), licenced under the

IWM Non Commercial Licence

Walter Tull ©

Northampton Town Football Club

Still from the documentary 'Battle of the Somme' ©

IWM (Q 70167), licenced under the

IWM Non Commercial Licence

Hasting Lees-Smith by unknown artist © public domain

Officers wading through mud in a fallen communication trench, 1918 ©

IWM (Q 10681), licenced under the IWM Non Commercial Licence

Wounded soldiers pavilion no. 1 at Northampton General Hospital ©

Northampton General Hospital Trust

Text in 'The wounded come home' section © Sue Longworth, archive volunteer at the

Northampton General Hospital Archive

The National Shell Filling Factory at Chilwell, Nottinghamshire ©

IWM (Q 30032), licenced under the

IWM Non Commercial Licence

Sleeping quarters for German prisoners at Eastcote Camp ©

IWM (Q 64122), licenced under the

IWM Non Commercial Licence

Abington Park Museum ©

Nick Hubbard, licenced under a

Creative Commons licence

Sywell Aviation Museum ©

Rob Farrow, licenced under a

Creative Commons licence

Scroll ©

Northamptonshire Archives Service

War memorial © public domain

Northampton General Hospital Archives ©

Northampton General Hospital Trust